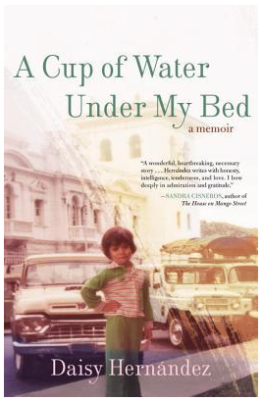

A Cup of Water Under My Bed – Daisy Hernandez

(April 2017) I loved this book for so many reasons. Daisy Hernandez is an American, born here to a Columbian mother and Cuban father. This book is called a memoir, but it’s so much more than that. It’s the chance to see the arc of a life in this country through a different lens. Hernandez is a gifted writer and above all else, the book is beautifully written.

(April 2017) I loved this book for so many reasons. Daisy Hernandez is an American, born here to a Columbian mother and Cuban father. This book is called a memoir, but it’s so much more than that. It’s the chance to see the arc of a life in this country through a different lens. Hernandez is a gifted writer and above all else, the book is beautifully written.

Her book is somewhat chronological starting with her remembered first impressions as a 5 year old child who speaks only Spanish being sent to a Catholic school in Union City, New Jersey. Her coming of age story has many things we consider common experiences, but it’s unfamiliar to those of us who do not understand the culture of her parents and their particular immigrant experience. I marked so many passages that jumped out at me as beautifully articulated thoughts intended to resonate with readers like me – those who want to understand how other people experience the world and how that feels.

“If white people do not get rid of you, it is because they intend to get all of you.

They will only keep you if they can have your mouth, your dreams, your intentions. In the military, they call this a winning hearts-and-minds campaign. In school, they call it ESL. English as a second language.”

Daisy Hernandez works hard in school and has an interest early in her life to be a writer. She earns a scholarship and attends college where she is introduced to feminist studies and meets a diverse group of young people including the first lesbians she has ever met. She is awakened to her own bi-sexuality. This is an important part of her story, but it’s only a part of it. This is an interesting observation about coming to terms with our sexuality:

“Generally speaking, gay people come out of the closet, straight people walk around the closet, and bisexuals have to be told to look for the closet. We are too preoccupied with shifting.”

She has relationships with men, with women and with transmen. This is in the late 1990s when such lifestyles are hardly mainstream. It’s important to know that this community has been there for a long time. Her relationships are important in how she sees the world. It causes her mother great pain and upsets her close relationships with her three aunties. They cannot understand this.

The chapters in her book are shaped by addressing different aspects of her life – she is a Latina, she is bi-sexual, the first in her family to go to college. When she gets a summer internship at The New York Times on the editorial board, a colleague remarks she is probably the first person to ever work on that board whose parents don’t speak English. She notices how little diversity there is at the Times, not just racially, ethnically and gender-wise but people who are of a different socio-economic status from the one her family is in. “We belong to a community based in part on the fact that we are all doing somewhat badly.”

She talks about learning of a concept in high school her teacher calls “Keeping up with the Joneses.”

“It takes years for me to understand that the Joneses happen in houses where people cook in one room and eat in another. The Joneses do not happen in places where people are called white trash and spics, welfare queens and illegals, and no one asks the Joneses if they are collecting.”

Her relationship with her Cuban father is complicated by many things – his struggles to keep a job as factories close all around them, his alcoholism, his rages. “It will take years to understand that writing makes everything else possible. Writing is how I learn to love my father and where I come from. Writing is how I leave him and also how I take him with me.”

When Hernandez realizes there is not a place in the hierarchy for her where she is, she decides to make a career move that takes her across the country to Oakland, CA. She lived at home for 27 years before moving into New York City and now she making a move across the country. It is what many of us would call a leap of faith.

The bravest phrase a woman can say is “I don’t know.” That’s my answer when my mother asks what I am going to do with my life if I am leaving The New York Times. I don’t know.

Daisy Hernandez has written a book that is captivating for it’s beautiful writing, its honesty and for a sharing of intimate thoughts that are likely shared by many and spoken aloud by few. The foundation of her memoir is holding close the family she loves so dearly while understanding their expectation of what her life will be in this country – their hopes for her and her dreams for herself.

“You have to study,” he says, his brown eyes dull and sad. “You don’t want to end up like your mother and me, working in factories, not getting paid on time. You don’t want this life.” His life. My mother and my tias’ lives. And yet I do – though not the factories or the sneer of the white lady in the fabric store who thinks we should speak English. I want the Spanish and the fat cigars and Walter Mercado on TV every night. To love what we have, however, is to violate my family’s wishes.

Years later, an Arab American writer smiles knowingly at me. “You betray your parents if you don’t become like them,” she tells me, “and you betray them if you do.”

I enjoyed every minute of this book. I would highly recommend it.