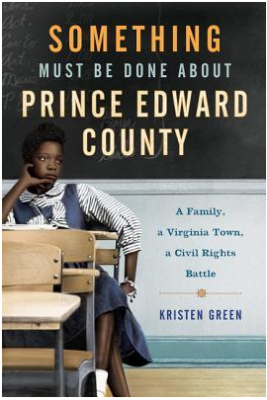

Something Must Be Done about Prince Edward County

The author discovered that her grandfather was instrumental in the massive resistance movement that closed all the public schools and created a whites only private academy. Black school children were shut out of getting a public education from 1959 to 1964 while Green’s own parents attended the private all white academy funded by “tuition grants” paid out of county tax money. Her own education and that of her brothers was also in that same private academy. Her sense of guilt and her search for meaning is palpable throughout the entire book. I believe that in researching and writing this book, she is engaging in an act of atonement.

For those who have seen the Civil Rights memorial at the Virginia State Capitol, just a short distance from the Governor’s Mansion, you will recognize the name Barbara Johns who led a student walkout at Moton High School in 1951. The former Robert Russa Moton High School is now a Civil Rights Museum in Farmville – the only Civil Rights museum in Virginia. Quite ironically, the only Vice-Presidential debate between Tim Kaine and Mike Pence will be held at Longwood University on Oct. 4th, just down the street from the Moton Museum.

The additional twist? That Civil Rights monument at the state capitol honoring Barbara Johns and acknowledging what happened in Prince Edward County was unveiled in 2008 by then Governor Tim Kaine.

Virginians need to know their own history and to acknowledge the damage done. In 1965, thirteen private whites only schools attended by more than 5,600 white pupils were operating in Virginia. In some communities, the public schools have never quite recovered from the resistance to school desegregation. The author’s own multi-racial children attend public schools in Richmond where she can see the effects of race, poverty and the lack of community investment in the school system.

I think the book is well written with great insights into a community where the author has deep roots and deep ties with the people still living there both white and black. This is a passage that really resonated with me:

While many of the people I’ve talked with are sorry the schools closed, I sense there is still a disconnect between regret about what happened and empathy for the people it happened to. I think of a story a friend shared about teaching her young son not to apologize. After he knocked over a classmate on the playground, he mumbled “Sorry” under his breath. My friend pulled her son aside and told him the apology alone wasn’t enough. He also needed to inquire about the other boy, listen to his response, and help him get up.

It’s as if Farmville didn’t get this lesson. The apologies to students shut out of school have never been adequate. Sometimes the community reminds me of a child who expects everything to return to normal once he says he is sorry. In this way, the town never grew up.

I agree it’s not enough to simply move on without acknowledging the role our history has played in the reduced opportunities now faced by many African-Americans in communities throughout the Commonwealth. We have not resolved the issues of racism that impact our schools and detrimentally affect minority students. We need to more fully understand how we got here so we can create a better path forward.

This book is a gem and I highly recommend it.